Introduction

Implementing all sort of methods to bypass anti-virus (AV) scanners and/or to make the analysis of a malware sample a lot harder, at least from a static point of view, is an old dog’s trick.

At LRQA, we see a lot of these techniques in evidence in malware that we come across during client engagements or that we personally collect via honeypots and other means.

Dealing with packers, either known or custom ones, is quite often an issue that any malware analyst has to deal with. Successfully unpacking and isolating the malware from the top protection layers can be really useful since it allows the analyst to concentrate only at the code that matters, and perform more detailed static analysis on the sample itself.

The Custom Layer

It doesn’t take much to realise that something is ‘wrong’ with this sample. Just by looking at the entry point of the module, an experienced eye will definitely blink.

Entry Point:

CALL 00401015 POP EBX MOVD MM5, EBX MOVD ECX, MM5 ADD ECX, 2C6 JMP ECX

This jump takes us to a custom decryption code block. Not surprisingly, this is heavily obfuscated with a lot of junk instructions.

The following code block shows a few effective instructions surrounded by junk code.

For example, if you take a look at the first three instructions, the ‘ADD ECX,EBP’ instruction is a junk instruction. These three instructions can be re-written with just one: “MOV ECX,EDX”.

PUSH EDX ADD ECX, EBP POP ECX MOV EAX, ECX MOV CL, 0CA XCHG CH, CH ADD EBX, EAX ADD EBX, DWORD PTR SS:[ESP] AND ECX, D73E1285 LEA ECX, DWORD PTR DS:[E58CFC96] MOV EAX, DWORD PTR DS:[EBX] XOR ECX, EAX CMP EDI, 0E2E4 JS 00401D4A INC ECX JO 00401D51 00401D4C BD 6149A0AD MOV EBP, ADA04961 MOV ECX, EDI MOV EBP, EBP IMUL EBP, EDI, CE86F98B SUB EAX, ECX BSWAP EBP MOV CH, AL MOV ECX, F7F0D4F3 MOV DWORD PTR DS:[EBX], EAX MOV CL, 0CC JE 00401D72 LEA ECX, DWORD PTR DS:[15F75C0D] SBB CL, BH

Once the custom decryption algorithm has finished its job, the execution will be transferred on the decrypted code block.

This stage of the custom packer acts as a loader. It will make use of a combination of CreateFileMapping/MapViewOfFile functions to allocate memory and copy there at the very same stage.

In the meantime, the authors didn’t forget to use some ‘funny’ names for the file mapping object: “Sessions1BaseNamedObjectspurity_control_7728”.

However, execution will never be transferred on that memory block and it will continue executing that stage from the original memory pages.

The next step is to create a new thread that will handle the final stage of this custom packing layer.

Thread Entry Point

ENTER 0, 0 MOV EBP, DWORD PTR SS:[EBP+8] CMP BYTE PTR SS:[EBP+402773], 1 JNZ 00402AF6 MOV ECX, DWORD PTR SS:[EBP+402774] DEC ECX TEST ECX, ECX JE SHORT 00402A15

This stage will finally make use of VirtualAlloc to copy the decrypted UPX-packed malware and pass execution to the entry point of the UPX packer.

However, there is a problem to solve at this stage. The execution is transferred out of the PE image memory range of the executable we are debugging. This can further confuse some unpacking tools since they will be trying to read information from the PE header of the original module in memory.

Even though there are techniques that an experienced unpacker can use to force those tools to read the information that they want, there are also cases like this one in which a simple trick can solve a big problem.

As already mentioned, the entire decrypted UPX-packed malware is now copied to another memory location. It is basically an entire PE file loaded in memory in the same way that would be if we had read the file from disk into a buffer.

So before proceeding into the next packing layer, we can easily dump and isolate the UPX-packed malware from memory so that we won’t have to deal with the first custom layer again.

Unpacking UPX

After we have dumped the UPX-packed malware from memory we can directly load this back to the debugger since it is basically a fully functional PE file. In summary, the custom packing layer is totally out of the game at this point.

Unpacking UPX is straight forward, and you can easily find a number of tutorials online that explain how it can be done, but since we are here let’s show this one more time.

UPX entry point

PUSHAD MOV ESI, 004AD000 LEA EDI, DWORD PTR DS:[ESI+FFF54000] PUSH EDI OR EBP, FFFFFFFF JMP SHORT 004B7AE2

The above code block is a common UPX entry point. Nothing really interesting here, apart from the fact that if you are familiar with UPX you can easily identify what you are dealing with.

Finding your way to the original entry point of the packed application is really easy. All you need to do is to scroll down the code until you find the following instructions.

Jmp to OEP

POPAD LEA EAX, DWORD PTR SS:[ESP-80] PUSH 0 CMP ESP, EAX JNZ SHORT 004B7C9C SUB ESP, -80 JMP 00434567 // JUMP to Original Entry Point. Place BP here and run.

OEP

PUSH EBP MOV EBP, ESP SUB ESP, 194 MOV DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-194], 0 PUSH 8002 CALL DWORD PTR DS:[40113C] ; kernel32.SetErrorMode LEA EAX, DWORD PTR SS:[EBP-190] PUSH EAX PUSH 2 CALL DWORD PTR DS:[4011EC] ; WS2_32.WSAStartup

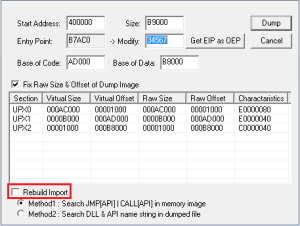

In order to dump the unpacked PE file from memory we used the OllyDump plugin, but you can you can use others as well. However, if you use this one, remember to copy the RVA of the entry point (highlighted in the Figure 2) and also uncheck the ‘Rebuild Import’ since we will be using another tool to do so.

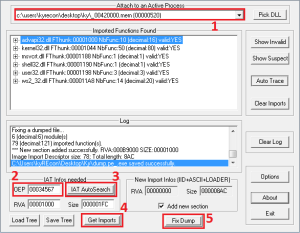

After we have saved the output in a file called ‘dump.pe’, we need to fix the imports table so that the dumped executable can load and run.