Anthony Alexander reviews the shale gas and oil development conundrum.

Recent extensive disparate and emotive press coverage has described how shale oil and gas production will either solve the world’s energy needs or how it will cause untold damage to the planet.

Recent extensive disparate and emotive press coverage has described how shale oil and gas production will either solve the world’s energy needs or how it will cause untold damage to the planet.

The main issue associated with a shale oil or gas development that has caught the public’s attention is the fracking process. This involves drilling a horizontal well then pumping water, sand and chemicals at high pressure into a shale deposit to open fissures in rocks and release gas and oil. Typically a horizontal shale well requires anywhere between two million and four million gallons of water for fracturing. Fracking immediately gives rise to two challenges, sourcing water for the fracking operations and then disposing of water which is back-produced from the subsequent well clean-up activities.

Hot debate

The discussions and debates have become ideological with proponents emphasising the potential economic benefits and adherence to regulatory requirements and the opponents emphasising the potential safety, social and environmental impacts.

Shale gas is either viewed as an unsustainable, over-hyped and desperate venture, with a legacy of environmental damage and associated public health risks that adversely impacts the local community, or viewed as a critical component of securing energy independence and balance in the face of rising costs and dwindling oil and gas reserves. Shale gas will either boost a country’s balance of payments or it is uneconomic and bound to fail.

With such opposite and diverse views how is it possible to form a balanced opinion about the issues, risks and opportunities of oil and gas production from unconventional oil and gas formations?

The facts

Shale gas and oil are trapped within often thinly layered and splintery rocks. They differ from conventional hydrocarbon reservoirs in that shales are largely impermeable; gas and oil will not flow naturally from them when a well is drilled and they require stimulation, usually involving fracking, to enable production.

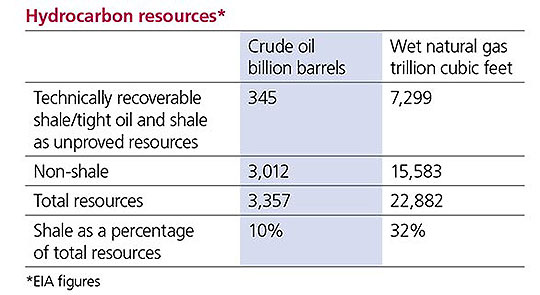

There are estimated to be large global quantities of hydrocarbons held within shale formations, the latest US Energy Information Administration (EIA) figures show technically recoverable resources of 345 billion barrels of world shale/tight oil resources and 7,299 trillion cubic feet of world shale gas resources. This represents 32 per cent of the total estimated natural gas resources and 10 per cent of estimated oil resources.

Shale oil and gas is located around the world with over half the known shale oil reserves in Russia, US and China and over half the shale gas reserves in China, Argentina, Algeria, US and Canada. In the US, many formations have widely differing gas/natural gas liquids (NGL)/oil ratios making forecasting and economic evaluation of the asset very difficult until a sufficient number of wells have been drilled. While in Europe and China the shale deposits are generally more gas-prone.

Nothing new

Shale gas and oil production is nothing new and, in fact, is one of the oldest sources of hydrocarbon in industrial development. It helped to power industrial growth during the 19th century when shale oil production was very much a ‘conventional’ hydrocarbon extraction process.

Travel from Edinburgh to Glasgow in the UK and you cannot miss the huge shale ‘bings’ in West Lothian. Now being colonised by trees and scrub, these 90-metre-high red spoil heaps are the visible remnants of Scotland’s original oil industry, predating North Sea development by more than a century. From 1851, James ’Paraffin‘ Young produced oil from coal and later from shale in the world’s earliest commercial oil refineries in central Scotland.

Early extraction methods relied on mining the shale and heating it to extract the oil before dumping the shale waste in bings. Thermal extraction is still a widely applied method, utilised both in a more efficient version of the Victorian mining approach or by the injection of steam into heavy oil reservoirs onshore to increase the temperature of the oil, reduce its viscosity and improve the efficiency of its production from long horizontal wells.

The market today

Shale gas now accounts for 40 per cent of US domestic gas production. The EIA Annual Energy Outlook 2013 forecasts a 44 per cent increase in US total natural gas production from 2011 through 2040 with shale gas production the greatest contributor, growing by 113 per cent.

Considering how various countries have approached shale gas developments clearly illustrates the fracking conundrum. The French government is ‘totally opposed’ to hydraulic fracturing, viewing that it is too ‘risky for the environment and health’. The UK government is actively encouraging production from unconventional formations with tax incentives being offered on fracking profits.

In Poland, the first exploration well was drilled in 2010 and to date around 51 wells have been drilled, however, no field has been commercially developed. This is due to a combination of the geological structure turning out to be more difficult to frack, with lower permeability than expected, and complex regulatory requirements. In January 2014, the Polish environment minister, promising to remove regulatory hurdles, said the country could see its first commercial shale gas as early as this year.

Recent reports suggest Australia could be set to be the next country to see major shale oil and gas development. It has the seventh-biggest potential shale gas resources and sixth-biggest shale oil resources in the world. The Cooper Basin, with existing gas processing and transportation infrastructure, may be the nation’s first commercial source of shale oil and gas, according to the EIA’s report.

Challenges to development

However, serious environmental incidents associated with shale gas drilling and production have occurred. Recently, the US Geological Survey has concluded that the release of hydraulic fracturing fluid into a Kentucky stream in 2007 was likely to be responsible for a die-off of fish that occurred after the spill, including a federally threatened species.

Experience from the oil and gas industry over the past 50 or more years has shown that you cannot just pick up the way of working, the design and the standards applied in one country and repeat it directly in another geographic location. Each location will be different with different technical challenges, different shale deposit characteristics, different environmental issues and different regulatory framework.

Controls for safe sustainable production

Considering all factors it is difficult to imagine that all governments across the globe will not resist the potential allure of production from shale formations to provide a degree of independence of their energy needs. If that is the case and companies can establish that a formation will be economically viable to develop, what controls should be put in place to ensure safety to life and the environment, safeguarding the welfare of the local community and ensure the integrity of the shale deposit and the asset? The June 2012 study conducted by the Royal Society and the Royal Academy of Engineering on behalf of the UK government concluded that fracking is safe ‘as long as operational best practices are implemented and robustly enforced through regulation’.

Areas that need to be considered for a shale gas development include design and operational safety, shale deposit management, the use of and risks to environmental resources (air, water and ground), the impact of infrastructure, logistics management, and community aspects; none of these issues are new for the oil and gas industry. The necessary skills are in place to perform the services required for safe and efficient production but it is imperative to recognise the community concerns and sensitivities that surround these developments.

Specific fracking concerns tend to be focused on groundwater pollution and disposal of chemicals and produced water. New technologies can address many of the environmental and economic concerns; fracking with hydrocarbon liquids such as butane can minimise requirements for water abstraction and disposal, while dynamic modelling and drilling wells to minimise formation damage and limit the scale of fracking operations can allay concerns and minimise costs (fracking accounts for around one third of the total well cost).

The shale gas and oil debate will consume forests of wood pulp for some time but the valid concerns regarding public and environmental safety can start to be addressed by robust regulation, prudent well design and safe operating practices. As always, safety, environmental impact and social impact must be paramount if this natural resource is to be exploited.

Anthony Alexander is Technology Manager Joint Industry Projects and Upstream Sector Leader, LRQA Energy